Ch 8: Successful Management of your Marketing Budget

5 financial fundamentals that every marketer needs to understand

Remember that accounting training you got when you went into marketing? Probably didn’t happen, right? 😏 Even though most marketers don’t always get the training they need, it is important that everyone responsible for significant marketing spend understands a few key accounting principles, and how those principles apply to their marketing budgets.

This chapter introduces five important pieces of information you need to know before you create and spend your budget: cash-basis accounting, accrual-based accounting, expense recognition, roll-forward, and use-or-lose-it.

If you understand these concepts, you will protect your budget, yourself, your team, and your company, from the unwanted consequences of major over- and underspend in your marketing budget. 🤓

Cash-based vs accrual-based accounting

Most articles you will read about these two different types of accounting focus on revenue and expenses. For most marketers, the focus is primarily on expenses alone, so that will be our focus. Given that, what does it even mean to account for an expense? Investopedia describes accounting as, “the practice of recording financial transactions pertaining to a business.” 🤷

There is a parenthetical phrase that I would add to make this more useful: accounting is the practice of recording financial transactions pertaining to a business, in the most informative way possible. Accounting helps explain what has happened financially in the business, so it needs to be comprehensible and clear.

There are two high-level approaches to accounting, each described below with their pros and cons.

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting records expenses when they are paid. This is normally not the most informative method of accounting. 👎

In cash-based accounting, the relevant expense hits the financial books at the time the funds leave the company bank account. In some ways this seems intuitive. It is how most of us are used to managing our personal finances. And if you’re running a lemonade stand, it might still be a good approach! But for most companies, it’s not particularly useful. Why? because there is often a separation in time between the cash outlay and the activity that generated the cash outlay. And this approach builds that difference right into the company’s books. If accounting is supposed to tell the story of the business, this approach obscures the real story. Because the date a bill happens to be paid is hard to predict, doing cash-based accounting creates a narrowly accurate, but somewhat arbitrary record of the business.

While a business may well want to pay for something 6 months after they received it, it doesn’t want to account for it that late, because it’s just too difficult to keep track of what that expense was for, when you consider the large number of diverse expenses the business incurs over time.

Finally, the gold-standards for business accounting – GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) and IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) – do not support cash-based accounting, and most companies don’t want to report their accounts in non-standard ways.

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting uses the notion of value to account for expenses. This method is required for GAAP and IFRS accounting. In accrual-based accounting, marketing costs may be recorded differently depending on what they are. Certain costs, like printing jobs, will normally be recognized upon invoice. On the other hand, recognition of event expenses will often be deferred until the date of the event, and all recognized on the same day as the event.

Why does it make sense to recognize expenses on different dates? The idea is to make the state of the business clearer to observers (executives, investors, auditors, etc). By aligning expense recognition of event costs with the date of the expense itself, it is easier to discern how much the event cost. If all the expenses in the run up to the event were recognized as they came in, it would be almost impossible to discern from an accounting system what the event actually cost.

So in accrual accounting, there is an association — a matching — between when an expense is recognized in the company accounts, and when the company receives value. Finance teams try to adopt a consistent approach about when the various types of expenses are recognized for their company, but companies have some latitude about how they operate as long as they are consistent. So as marketers move from company to company throughout their careers, they need to understand how each new company does things. It’s important for marketers to understand the timing of expense recognition within their company so that they can plan accurately.

Example

ACME wants to run an ad campaign on TV. ACME outsources 100% of the ad production costs ($500,000) to AdAgencyCo. It purchases a $1,000,000 mediabuy on a TV station. ACME receives the invoices for the ad production and the media buy on the same day. That date happens to be after the production is complete, but 2 months before the ads will air on TV. The $500,000 production costs are recognized when the invoices are received, because the value received by the company is the finished ad. So the bills for the ad production must be recognized when production is completed, regardless of whether – or when – the ad airs. The $1,000,000 mediabuy is recognized in the books two months later, when the ad is aired. It is important for the marketers at ACME to understand when the costs for their campaign will be recognized, otherwise they might find expenses hitting their budget in unexpected time frames (Note: this is not the only way the investment can be accounted for in an accruals based approach, but it is one valid method that is provided as an example in GAAP guidance to help illuminate time-based recognition of different marketing costs).

Sometimes an accounting team might accrue an expense before an invoice is even received. It might do this if there is a highly predictable billing cycle and well-established value for a given bill. For example, many companies have contracts with SaaS companies that invoice on a monthly basis. The SaaS contract may call for payment of $1,000 on the 1st of every month. Accounting may well decide to accrue the $1,000 expense even if the invoice hasn’t arrived by the first of a given month. This makes sense, because there’s a legally binding contract in place that stipulates a $1,000 expense every month. If nobody canceled the service, there’s surely a bill coming: it’s common sense to account for it.

This method of accounting makes business finances more readable, traceable, and understandable for everyone, because it shows expenses as being accounted for in the same time period as the value received. That matching principle is a cornerstone of good accounting.

Summary

Cash Accounting – one method, simple, but not that informative

- Service delivered → invoice received → invoice paid/expense recorded

Accrual Accounting – various valid methods, more complex, expense tied to value

- Service delivered → invoice received + value received + expense recognized → invoice paid

- Invoice received → service delivered + value received + expense recognized → invoice paid

- Service delivered + value received + expense recognized → invoice received → invoice paid

👏 WHY 👏 DOES 👏 THIS 👏 MATTER 👏 TO 👏 MARKETING 👏 BUDGETS? 👏

I know, I know. This is not why we became marketers. But it matters a lot. Here’s why: your marketing budget is distributed over time: that could be months or quarters. There is some allocation of funds in the plan that assumes you will spend the budget at a certain rate each time period. Your goal is to spend it down to the last penny (but no more) and to spend it on the most goal-aligned activities you possibly can. If you don’t know how your expenses are being accounted for, then you don’t know what you’ve spent for a given time period’s budget. Look at this treatment of the same expense under cash-based vs accrual accounting

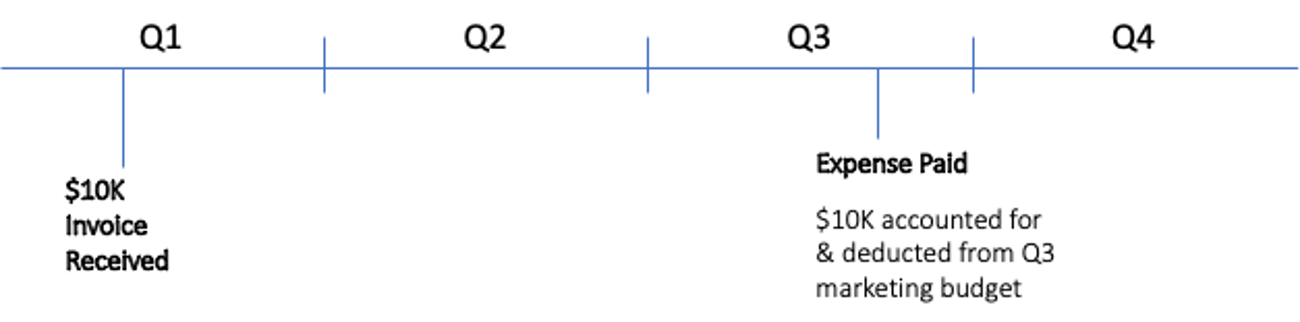

Cash Based

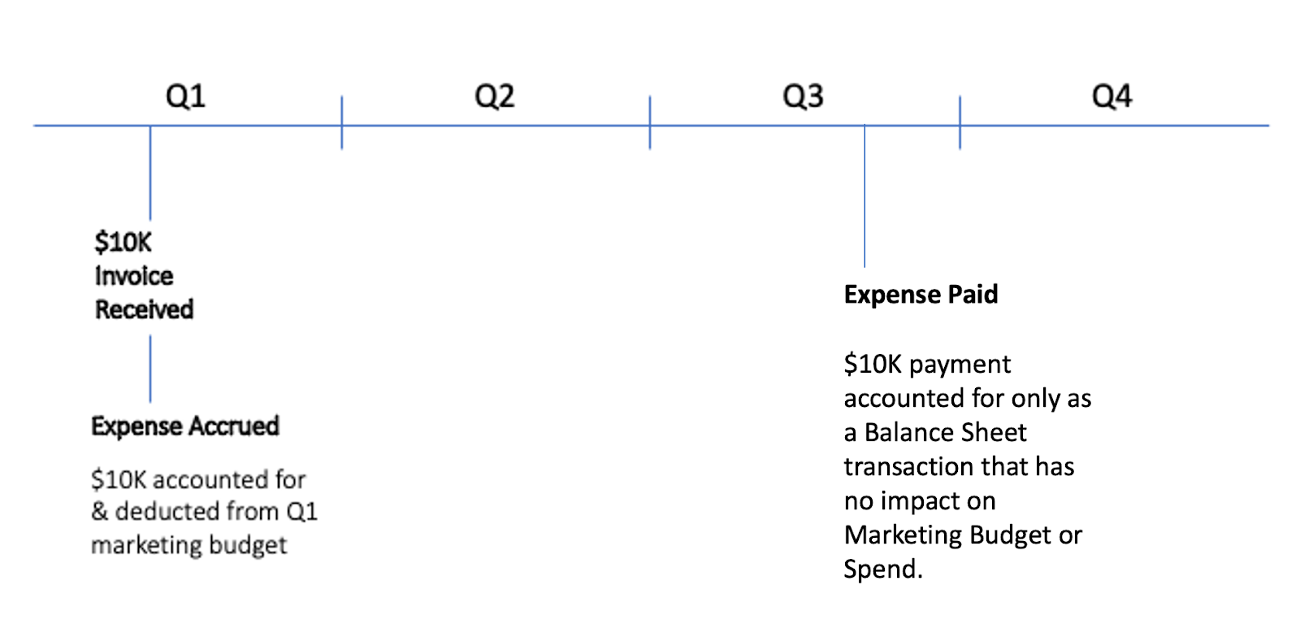

Accrual Based

In cash-based accounting, the expense was deducted from the Q3 budget. In accrual accounting, it was deducted from the Q1 budget. For most marketers, the accrual based system makes much more sense: their expenses are accounted for when they are invoiced. This is much easier to plan for and manage in order to manage spending accurately. As a marketer, you should not need to care when the cash has left the company bank account, or what the CFO is doing on the Balance Sheet!

Spotlight: Expense Recognition in Accrual Based Accounting

There is one other critical element of accrual based accounting that is important to familiarize yourself with: when are expenses recognized? Didn’t we just say they’re recognized upon invoice? Not quite – we said they’re accounted for upon recognition of value. It is possible that you might be invoiced for a service, may even pay for a service, before it delivers business value. The most common marketing example of such an instance is events.

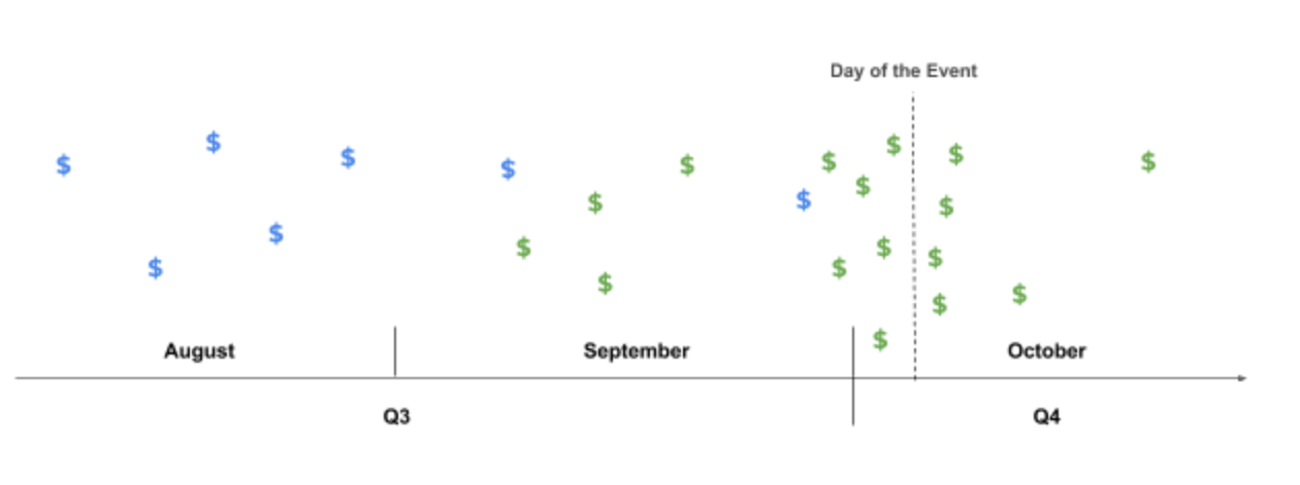

Consider the diagram below, where marketing incurs multiple expenses in the run-up to, during, and even shortly after a trade show.

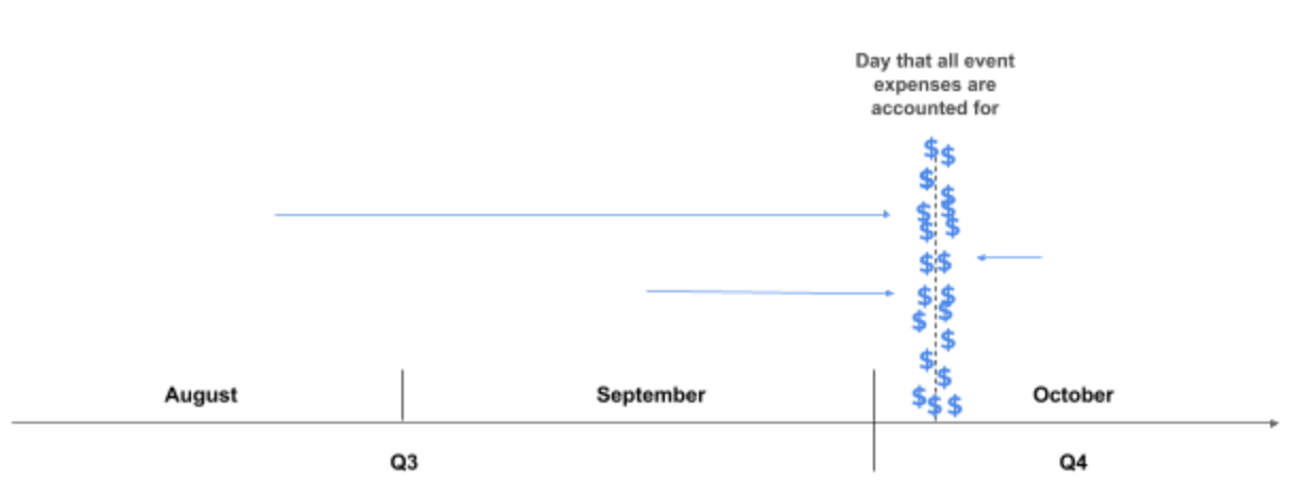

The blue expenses represent those that have been invoiced and paid. The green expenses represent expenses that have not yet been invoiced and/or paid. Under accrual-based accounting, it is possible that 100% of these expenses will be recognized by the company on the day of the event because this is when the company received value for all of the expenses related to the event. From an accounting perspective, that looks like this:

Suddenly we see expenses appearing in what might feel like the wrong quarter again, even under accrual-based accounting. Confusingly, expenses that the marketer knows have been paid may be moved in the company accounts to align with the event date (i.e. when the value was received). In the finance report of expenses, this will normally show as a negative value (e.g. -$50,000) in the time period where the expense was originally paid and a new, equivalent positive value on the date of the event. Nothing has really changed other than the date the company has decided to account for the expense, but you need to know whether and how that impacts your marketing budget – preferably when you create your plan.

It’s important that the marketing team knows when accrued expenses will be recognized so that they know (1) how to budget accurately at the beginning of the year (2) when expenses will be deducted from the budget, no matter when the invoices land.

At a minimum, marketers should be sure to understand how expenses for campaign types that trigger deferred expense recognition – like trade shows – are treated by finance. Failing to do so could lead to significant underspend in certain quarters (i.e. you thought you were accruing event expenses but you weren’t) and significant overspend in others (i.e. all the expenses for an event hit at once, and you thought you’d already paid for them).

Understanding expense treatment for your budget is not just a CMO responsibility – all marketers running campaigns (especially events) and spending the company’s money need to have a keen sense of how their investments are accounted for.

Roll-forward vs Use-it-or-Lose-It

Some companies set a budget for the year, and if not all of the anticipated Q1 budget is spent, the difference is rolled forward into Q2, and so on through the year.

Others operate on what is known as a use-it-or-lose-it basis. If you fall into this camp, the need to understand how expenses are accounted for is even keener. Under use-it-or-lose-it budgets, there are normally soft boundaries between months (e.g. unused budget from January can be rolled into February) but hard boundaries between quarters (e.g. unused Q1 funds are taken back by the company, and the Q2 budget remains unchanged).

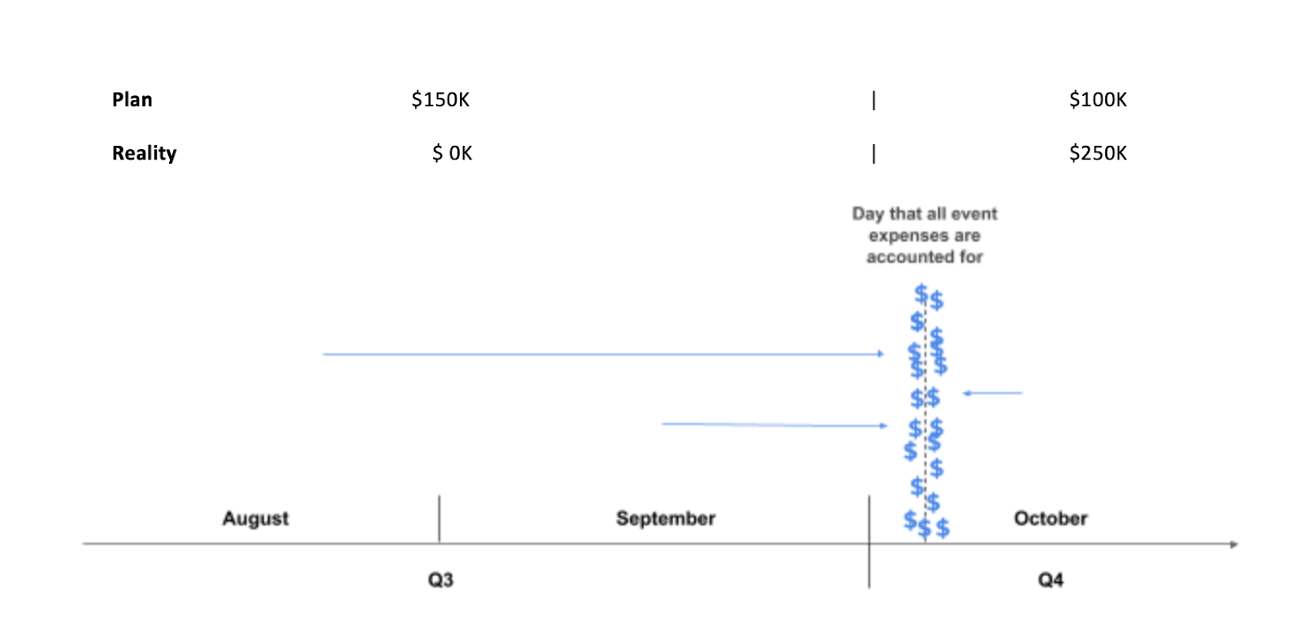

Returning to our event example in the previous section, imagine the the total cost of that trade show was $250K. The marketing team anticipated that $150K would come from the Q3 budget and $100K would come from the Q4 budget.

Unfortunately, the entire $250K came from Q4. Under use-it-or-lose-it policy, the $150K underspend in Q3 is taken back by the company, and the Q4 budget has an unexpected additional $150K of closed expenses to fund. That means Q4 needs to be radically replanned at very short notice or the budget will be badly over-spent.

If you work in marketing or marketing operations, you should make sure you’re familiar with the accounting concepts covered in this chapter so that you can have a clear understanding of how and when expenses will hit your budget. If you understand these concepts, you will be able to plan and execute more accurately. This will help you and your team ensure you spend your funds promptly, confidently, and on the most important things. ✊👌💪

Most marketing budgets are losing 0.8 – 2.1% of their budget to subtle forms of waste accumulated from numerous small issues.

A free(ish) vacation every year

When I was growing up, my father used to save for family vacations by putting the small change he had in his pocket at the end of the day into a large glass jar. When the jar was full, we would empty it out onto the floor to sort and count the coins and tally up its contents.

Every year we were absolutely floored by how large the total was. How could these tiny – borderline worthless – increments add up to something as meaningful as a vacation? Every year it worked. And every year we’d be left shaking our heads, grinning at each other about what felt like a free holiday. But of course it wasn’t free – it was enabled by what I call the Law of Small Change (LSC).

Looking back, I think the key to LSC working was the discipline my dad had about the process. Every day, without fail, when he got home from work, he’d retrieve whatever coins were in his pocket and drop them into the jar. Every day. Without fail. If he’d only done it occasionally, the jar’s contents would never have amounted to anything. If he’d left the coins on a side table from time to time instead of putting them in the jar, we’d have had the same amount of money in the house, but our vacation fund wouldn’t grow enough and we’d probably have ended up doing…well…nothing with it. That’s important. We’d probably have just ended up with a lot of medium sized piles of change knocking around the house that didn’t get spent. It was the consistency, the repetition, the routine that made it happen.

“How is this relevant to marketing budgets?” you may be asking. Fair enough.

The LSC at work in Marketing Budgets

Marketing teams accrue piles of small change at amazing velocity and in diverse ways. There’s no other function in which so many people are empowered to spend so much and so quickly. We’re going to highlight nine key ways in which marketing leaves small – and sometimes not so small – cash stranded in the nooks and crannies of its marketing budget. And we’ll highlight how these piles add up to shockingly large totals.

One thing to be clear about at the outset: these losses are not due to negligence or incompetence. Rather, they’re the inevitable outcome of legacy tools and platforms that are unfit to manage marketing budgets, which are complex and change a lot. We built our marketing budgeting management software to solve these problems.

Here are some of the key factors. We know these are both real and significant because we onboard and manage hundreds of real marketing budgets, and our marketing database – the Plannuh Marketing Graph – shows us the facts.

- Not reviewing the marketing budget regularly. A marketing team should spend every last cent of its budget in the most thoughtful way possible, and not a penny more. Marketing teams that don’t regularly review the status of their budgets and maintain a current view of the state of the budget don’t have a chance of doing this. Most months, they will overspend or under-spend, culminating in a major miss by the end of the year. One of our customers reported that before using Plannuh, they reached the end of the fiscal year to be told by finance that they had underspent by tens of thousands of dollars on a budget of less than $1,000,000. That money could have delivered meaningful business results. The VP of Marketing didn’t know because they didn’t have a process and platform that supported a current view of the marketing ins- and outs.

- Not reviewing the budget as a team. We requested a customer bring their entire marketing team to a training session, which was unusual for them. During the meeting, as we reviewed their budget in Plannuh, a budget owner piped up, “This is awesome. I didn’t even realize I had a $50,000 budget in Q2.” Why didn’t they know? This was a smart team run by a strong VP of Marketing. There were a few reasons, but the main one was that they did not review the budget as a whole team. There were people with buying power and budget responsibility who didn’t know what they were empowered to spend and when.

- Budget spread over multiple worksheets. A customer walked us through their budget spreadsheet prior to onboarding to Plannuh. It looked like a work of art. Beautifully laid out. Formulas pulling data from other worksheets. A separate worksheet for each budget owner, entering their data into a common template. The problem was that the totals on the individual worksheets didn’t match the totals on the summary worksheet. And the totals on the individual worksheets didn’t add up to the full budget target. It required forensic analysis and some black-belt spreadsheet skills to figure out all the errors. The problem is Excel fails silently. If someone hard-codes a number on top of a formula in one cell, enters a number as text in another, inserts a row that’s not included in a formula in another, etc, multiple little piles of wasted budget are distributed throughout this complex spreadsheet, hidden in plain sight. Every incremental worksheet, or – worse – spreadsheet, and every incremental user working in the spreadsheet, increases the frequency and likelihood of errors.

- Poor visibility into the budget. One budget we onboarded had run out of funds for two of its four divisions at the end of the eighth month of the fiscal year. Every penny in the last third of the year was 100% over budget. The budget owner didn’t know this because their spreadsheet – provided by finance – was so complex that it was genuinely difficult to understand what was contained within it.

- Stranded budget in completed campaigns and closed expenses. One company realized that it had 23% of its budget still available to spend. That’s not great. Worse, they had only 2 weeks left in their budget year to spend it – an impossible task. That 23% was an accumulation of numerous small deltas between planned and actual expenses, and small underspends in completed campaigns, that had accrued throughout the year. Just like the vacation money jar, they added up to a significant total, and could have added tremendous business value if they’d been easily visible to everyone on the team.

- Inaccurate budget tracking lost to use-it-or-lose policy. One of our customers routinely lost between 5% and 10% of their budget each year because they couldn’t spend their budget in time with their existing budget tools. They didn’t have a current view of what they had spent, so they were nervous to overspend as they approached the end of the quarter. Therefore they shied away from spending towards the end of each quarter. Once the expenses were reconciled, any remaining budget was lost for good.

- Overpaying due to multiple rush orders. Rush charges occur – most of the time, at least – when a poorly planned expense is incurred. Poorly planned means the team finds itself making an investment in something services-based and not leaving itself time to negotiate a fair price. Common examples of this are printing, design and booth needs for events. Typically the marketing team will find itself overpaying by at least 10% for such expenses.

- Not reconciling expenses with finance. One prospect who did not become a Plannuh customer (you’ll see why in a minute) was a CMO who told us that he did not reconcile any expenses in his multi-million dollar annual budget. We expressed surprise that this was so, since he acknowledged he had no way of knowing his current expenditure with any accuracy. His outlier status was confirmed when he stated that he was okay as long as the budget was “within about 20% of the target by the end of the year.” If your company is okay with your budget being 20% inaccurate, Plannuh is not for you.

If your company is not okay with that, then you need to reconcile your expenses (and we should talk). But just committing to reconciling them is not enough. You need to understand what you have spent as soon as possible. Unfortunately, turnaround time for expense reconciliation is painfully slow. This creates lots of small piles of stranded budget throughout the plan, which, as we’ve seen above, are difficult to track, and add to the cumulative budget risk.

- Making mistakes in expense reconciliation. One of our customers generated a 19% budget inaccuracy by – thanks to a spreadsheet design error – summing up their planned and actual expenses. While this is a gross error, there are numerous manual reconciliation errors that occur over the course of a year. Failing to close expenses. Closing them for the wrong amount. Accepting expenses from other departments. Logging expenses in the incorrect currency and so on. Every one of these errors leaves a small pile of wasted budget.

Hopefully these examples have illustrated that to get the most out of your marketing budget, you must track and manage that budget diligently, with regular, teamwide reviews of spending. You should maximize the freshness of your data, ensuring no budget is left stranded in campaigns or unclosed expenses. You should accurately and promptly reconcile expenses as soon as possible. This is almost impossible to do with spreadsheets, and is exacerbated by distributed and shared spreadsheets.

The PMG shows us that companies consistently generate cumulative budget risks of 15-25% annually due to an aggregation of the issues above, over the course of the fiscal year. In other words, they lose 0.8 – 2.1% of their budget each month to the Law of Small Change. There is a tremendous opportunity to reclaim that lost budget – the marketing equivalent of that free vacation. Who wouldn’t like a 15-25% budget increase?

Plannuh is designed to address the LSC. Get in touch with us to learn more about how much of your budget could be stranded, and how to reclaim it.

Budget Burn Rate as an Indicator of Marketing Execution Risk

We know that responsible marketing teams should not overspend. It causes P&L issues, can disrupt the marketing cadence if campaigns have to be canceled because the budget has been exhausted, and leads to general disharmony. Something less well covered but equally important is marketing underspend.

One of our favorite customers at Plannuh came to us because their finance team had told them that they were underspending chronically throughout the fiscal year. The problem was opaque to them because of their existing tools and processes: the typical combination of spreadsheet based marketing budget and episodic accounting system dumps from finance. It was impossible to have real-time visibility into what they had spent and what was left in the budget for that time period.

As they moved through the year, they didn’t know whether they could make that next significant purchase, or whether that would take them over budget, so they did what most responsible corporate citizens did: nothing. Better to be under-budget and safe than potentially over-budget, right? And they could always roll forward any unspent budget into the next time period and spend it then.

Unfortunately, this is not the right way to manage your marketing budget. You can’t endlessly roll forward unspent funds because the end of the fiscal year (or fiscal quarter) is a brick wall. At some point you find yourself upon the wall, and the unspent funds piled up against it are swept into the corporate coffers having added no value to the business.

That might mean the company saves a little money, but it also means the marketing team has demonstrated that it does not have the wherewithal to spend the budget it was allocated. Worse, they have not delivered the business benefits of the marketing investments they failed to make. This can raise questions about whether marketing is operationally sound. Since actual spending typically sets the baseline for the next year’s budget, underspend can lead to year-over-year reductions in marketing budget.

The Underspend Conundrum

Figure 1. The underspend conundrum

It is probably worth bringing to the fore a critical, but implicit point: marketing needs to spend 100% of its budget, spend it promptly, and spend it thoughtfully. If this seems obvious, it isn’t to the many marketers – and corporate cultures – who think it is a virtue to come in under budget. It is not. It’s a virtue to spend less on electricity than you intended, or to implement a corporate IT project under budget. But marketing underspend fails the business and can lead to unwanted consequences, as illustrated above.

If marketing underspends, then it breaks its compact with the company about what it is going to deliver in terms of pipeline, leads, brand enhancements, awareness and so on. In an ideal world, a marketing team spends every penny of its budget aligned with marketing goals and against a well-structured plan.

With the existing systems in place for managing marketing budgets at most companies, this is impossible. Note that I did not say it’s nearly impossible: it’s impossible in every practical sense. Most marketers discover somewhere between 6 and 8 weeks after the fact what they have spent. This time lag necessarily crosses monthly budget boundaries, and frequently runs into harder quarterly budget boundaries. If you don’t have visibility into what budget is available right now, and you know that heads will roll if you overspend, it is human nature to slow down in moments of uncertainty. If those moments of uncertainty are frequent enough, you will have the same kind of chronic underspend that our customer was experiencing.

The first step is to do what they did, and move your plan and budget onto software that provides real-time visibility into planned, committed and invoices expenditures. You don’t have to wait for the final payments to be made by finance, and then to receive the AP or open PO report to have that current visibility. You just need a system to track it. You can always interlock to the penny with the finance system once their reports land in your inbox but there is no need to fly blind in the meantime.

Another key step you can take is to get familiar with the concept of Budget Burn Rate.

Introducing Budget Burn Rate (BBR)

Before we introduce the concept of BBR, we are going to make and test a key assertion: that when a marketing leader finalizes their marketing plan and budget, they will have in place a staffing and resource capacity – or at least a capacity plan – to execute the plan and spend the budget within the fiscal year. Are there enough FTEs, contractors, consultants, agencies, tools, etc., in place to actually deliver the plan on paper? Our assertion is that for the majority of the time, the CMO has verified this, and believes that their plan and budget is efficiently executable with the resources on hand.

This is a critically important assumption to the concept of BBR, so it’s worth a moment to test the logic. Do we think that it is more likely or less likely that marketing leaders enter a year in the following states?

- The CMO has no idea whether or not they have the capacity to execute their plan and budget

- The CMO is knowingly overstaffed and could execute a much larger plan and budget than the one they have

- The CMO is knowingly under-staffed and knows they cannot execute the plan and budget than the one they have

We believe that for the large majority of marketing organizations the answer to all three questions is “less likely.” In other words, most CMO’s have some degree of interlock between their marketing budget and their capacity to spend that budget in a thoughtful way. We only care about this assertion in the abstract for now. While it’s true that a small team doing nothing but digital campaigns can burn through a huge budget quickly compared to a team that does nothing but field marketing and regional events, we believe that the capacity of a marketing team (not just FTEs, but all contract labor, agencies, as well) is normally at least roughly right-sized to the nature of the marketing plan, its required campaigns and tactics, and the size of the budget to support it. If you’re with us, read on.

What is BBR?

BBR is a function of change, like miles per hour, GDP per capita, calories per slice of pizza. In the case of BBR, we are measuring how much budget needs to be spent per time period for the remainder of the year in order to consume 100% of the budget accurately and thoughtfully (where thoughtfully means in alignment with the marketing plan). We’ve picked a day as the unit of time. It could be a week or a month, but the bigger the time unit, the less granularity we have.

Imagine you have a budget of $1,800,000 for a fiscal year. Regardless of how you intend to allocate the budget over time and by campaign, you need to consume that budget in the next 365 days. On day 1 of your fiscal year, your required average BBR is $1,800,000/365 = $4,932/day.

Now let’s assume that you decide to allocate your budget across the months like this:

It doesn’t matter that the allocations by month are different to each other, nor that the most expensive months require the team to consume 190% of the least expense month’s budget. We assume that there is a marketing capacity in place that is right-sized to consume this budget at this rate over the course of the entire year.

After January, there are 334 days left, and if the entire $100K that was budgeted for January has been spent, the required BBR for the remainder of the year is now ($1,800,000 – $100,000)/334 = $5,090/day. If the budget is spent perfectly, here’s what the curve for the daily BBR looks like over the course of the year:

Figure 2. Planned BBR with Min, Mean and Max lines

The dashed lines indicate the minimum daily burn rate, the mean daily burn rate, and the maximum daily burn rate required to consume the budget on-time, with a range of $4,932 – $6,129/day. As long as the burn rate stays within those bounds, the capacity of the team should be well sized to execute the marketing plan and fully consume the budget on time.

Now, let’s say that as the year gets underway, the team consistently spends a little less than planned each month. For this example, we also assume that any underspend is continuously rolled forward month-to-month.

Traditionally, this kind of delta would normally be portrayed using something like the chart below. In this chart, the blue line indicates the original plan, the red line indicates the cumulative actuals and the green line indicates the cumulative underspend. It doesn’t look that bad. At first blush it looks like the team tracked along roughly accurately but finished the overall plan fairly close to the original. In reality this is a 10.5% underspend – that’s a large discrepancy from the original plan. That most likely means that there are significant shortfalls in pipeline, bookings, leads, impressions, and so on that the business now needs to cope with.

Figure 3. Typical comparison of Planned vs Actual budget usage

This is also not a particularly helpful view analytically because it isn’t actionable. If we cast this same data onto a BBR view, however, we see something more alarming, more realistic, and more actionable:

Figure 4. BBR representation of Planned vs Actual, indicating growing execution risk over time

As the underspend accumulates over the year, we can see the required daily BBR (the red line) begins to increase and separate from the planned daily BBR (the blue line). In early August, the required BBR breaks through the maximum BBR for the year (remember, that approximates the maximum capacity of the team).

As the underspend piles up month to month, the required BBR accelerates away from the plan BBR. This is because the time available to spend the rolled forward budget is running out – the denominator is shrinking while the numerator is growing relative to the original plan. In plain English, there’s more money to spend than we thought there would be in a shrinking time frame. We’re about to hit the end-of-year wall.

Imagine you are the CMO running this budget and it’s November. You have a lot of money to spend. Your team is fully occupied executing as much of the plan as they can – but they’ve been consistently under-spending throughout the year. What are you going to do? You need to spend twice as much money as you normally spend through the rest of the year and your team is fully occupied. Look back again at the Underspend Conundrum flow chart above and you will see there are few good choices. Marketing teams find themselves in this position all the time.

BBR as a forecast of execution risk

Do we need to careen into the year-end wall, frantically trying to spend more money than we can – knowing we’re not spending it wisely? We believe BBR can help avoid these situations. As soon as we see the BBR begin to deviate above the plan BBR, we know we’re underspending.

As the gap begins to widen, the risk increases. Before it approaches our maximum team capacity we need to begin to increase our BBR so that we can pull the red line back into order to match the blue line. Perhaps we need to hire some more temp help, or open the throttle on that digital campaign. The remediation is case dependent but the value of bringing the current and plan BBR into alignment is clear – it means we can finish the year spending our money intentionally, phased appropriately over time, and in accordance with our strategic goals. If we’d been measuring BBR, we would have seen this move of the red line towards our maximum capacity early in the year, and been able to take action while we were still in the first half of the year.

Achieving your Marketing Goals is Impossible without Accurate Expense Management

An expense is an expense, right? In the sense that they all hit your budget, yes. In most other respects, not really. The team dinner check, the hotel block-booking for a trade show, the rush print job for the key customer visit, the dreaded expense that’s transferred in from another department, the CRM subscription…different types of expenses have very different life cycles. Some of them you can – and should – plan for. Some you need to know will happen anyway and accommodate in your planning.

There’s a pretty finite set of expense types that you will have to deal with. In this chapter, we’re first going to deal with the life cycle of a typical expense, and then we’ll talk about how different expense categories fit within – or occasionally violate – this life cycle. Once you know this, you will be able to look at the expenses in your plan and budget with a fresh eye, and make sure you’re treating them in the way that’s most useful to you and your team.

The Expense Life Cycle: Estimated→ Committed → Charged → Reconciled

Estimated – We have to estimate expenses all the time: we know we’re going to need to book some rooms and pay for some meals at that upcoming event; we’re going to need a creative agency for our upcoming campaign; we’re going to publish some billboards downtown. When we know about these expenses in advance, we should estimate what the expenses will be. Planned expenses should have estimated amounts

Committed – Some expenses will be large enough and far enough in the future that we decide to negotiate the price with a vendor. We may sign a contract to lock in that price along with other terms. You might sign up a PR agency for a campaign, a creative agency to help you prepare for an event, or a new technology platform to automate some of your marketing processes. Once you’ve signed the contract, you have a more precise view of the cost than your initial estimate, and you know you’re really on the hook to pay that money (unless the vendor somehow breaches the contract). You haven’t been invoiced, the service hasn’t been delivered, but you know you’re going to be paying a precise amount in the future. Negotiated expenses should have very accurate cost estimates.

Charged – Expenses are charged, from the marketers’ perspective, once the service has been delivered, or once an invoice has been sent. Note – the expense should be marked as charged regardless of whether or not it has been paid by finance. What the marketing team should care about first and foremost is how much budget has been consumed and how much is left. Surprisingly frequently, we have met marketers who are concerned about when and whether a bill has been paid. When a bill is charged against your budget is important to understand – see our article on accruals vs cash-based accounting to see why. But when a bill is paid is a finance team concern that does not affect how much marketing budget is left. Our recommendation is that you treat invoicing as the trigger to mark an expense as charged. Likewise, you should treat credit card expenses as charged.

Reconciled – There’s more after charged? Yup. The majority of marketing teams receive a periodic report from finance that includes the accounting system view of all the paid bills that have been charged to marketing. Most of the time this will contain line-by-line confirmations of what you already know and have in your plan. However, the final accounting of expenses may well contain changes that you need to know about and pay attention to, e.g.

- You didn’t anticipate the sales tax for your finally negotiated price, and the cost that finance has to account for is a little higher than you thought

- Finance has charged something to marketing that is a surprise to you – it wasn’t in your plan. This might include some credit card expense that you didn’t know existed until now; an expense transferred in from another department; a change of date to an expense due to accruals-based accounting

In any case, it’s imperative that you snap your plan into line with the finance team’s report to ensure that your pretty-darn accurate view of the charged marketing expenses ultimately lock in to the financial system of record. The problem is, you can’t wait weeks or months for those finance reports or you’re flying blind, and it’s impossible to spend accurately, decisively, and at the right budget burn rate. So you need to develop and manage the highly accurate team-sourced view of the reality of your charged expenses, well ahead of the finance report. Demanding accurate, real-time expense status from the entire marketing team will enable you to make fact-based, accurate decisions on time.

Now we have our model, and understand the stages, we’re going to review the different types of expenses and how to manage them to best achieve your marketing goals. Not all expenses go all the way through this process; some just appear at different stages – even at the last stage. We’ll cover those at a high level in the subsequent section, and then we’ll capture them all in a single model.

Carried-over expenses

When you enter your budget year, your budget will – should, at least – contain a number of expenses that are estimated, committed and possibly even charged and reconciled. You should try to get those into your plan in as much detail as possible so you have an accurate forecast of spend and a clear understanding of what’s left to spend. Examples of these include: campaigns that cross fiscal year boundaries; events that you do every year; subscription fees for data or technology; open PO’s for contractors, agencies, etc; corporate allocations; depreciation. Many of these expenses will be at least charged, and often reconciled on day 1 of the fiscal year.

Planned expenses

The way it happens in the marketing textbooks, and some of the time this is the way it happens in reality.

If you have a new campaign, set of expenses, or an individual expense that you know is new for the fiscal year, you should enter it into your plan with the most accurate estimate of the expense that you can manage. It doesn’t matter if it’s imperfect – it’s much better to have something in your budget than nothing.

Examples include event expenses that are known in advance (e.g. block room booking, travel, meals, booth expenses, printing, agencies, etc); a digital campaign with an estimated spend-per-day ceiling; technology and data subscriptions; contractor retainers, and so on. There are many unplanned expenses that will crop up through the year, so the more thoroughly you can add your planned expenses into your budget, the better your visibility into what remains to be spent, and how close to over budget you are.

Planned expenses may be large enough that you have to raise a PO, and negotiate price and payment terms, or they may be small, or fast-moving enough that they are charged to a credit card without a PO or contract.

Planned Expense Buckets – You may plan an aggregate cost for a group of expenses and reserve budget for them. In the Plannuh’s marketing resource management software, we call this an expense bucket. In this context, we use expense buckets to estimate the cost of a set of expenses for which it may not be possible – or a good use of time – to estimate the line-by-line costs for each individual expense. For example, you might budget an amount for travel every month even though you don’t know the precise make-up of taxi rides, train fares, air fares and car mileage that is going to come in. Such expenses will likely be charged to credit cards – maybe even paid by cash – and won’t be explicitly in the marketing plan with line-by-line precision. When you first see them as individual expenses, they will already be committed, or even reconciled, and they should be charged to the marketing budget you reserved for them as they come in.

Unanticipated expenses

No-one likes these, but they happen all the time. We normally become aware of these expenses when we receive our finance report. What’s unpleasant about these costs is that they are (1) unplanned by definition (2) often already charged and accounted for the first time you see them.

It makes a lot of sense to try to understand your surprise-expense run-rate if you can. If you don’t know what it is, look at some historical data and try to find expenses like this: accounting reclassifications (i.e. an expense is moved in to your budget from another department); corporate allocation you didn’t know about; someone did something bad with the corporate credit card and you have to eat the cost.

You may also encounter surprise expenses from unforeseen issues. You may have unexpected PR costs from a crisis management project (e.g. customer, press, investor and analyst communications after a data breach), for example, or you may have to make a major mid-year adjustment in your plan due to some major external factor, like a natural disaster.

Disputed expenses

When you get a surprise expense, you may conclude it doesn’t really belong in your budget. This is a very common occurrence, and it pays to be diligent – you have enough to worry about with paying another department’s bills.

Corporate and departmental allocations are frequent candidates to be disputed. You need to track the expense in your budget as if it’s going to be paid by you until finance agrees to move it.

Moving expenses

You planned it. You know what date the invoice arrived and how much it was for. You know it belongs to marketing. So why can’t you find it in the expense report?

As we’ve written about 5 financial things you need to know it’s important to understand how your finance team accounts for expenses. Otherwise you may find that expenses you thought hit your budget in one time period actually were applied in a different time frame. This can lead to inadvertent underspend or overspend, even if you’ve been diligently tracking your expenses prior to interlocking with the finance team.

The Unified Expense Model

The figure below is the unified expense model. It shows when during the expense life cycle different types of expense may be initiated, the evidence for their existence, and the phases they will occupy until they are reconciled. It’s possible that your expenses won’t work exactly like this. That will depend on the specific policies and practices adopted by your company.

What is important is that you and your marketing team understand how your expenses are handled for your company’s marketing budget. If you understand this well, you will be able to both plan and execute your spending with a high degree of accuracy to achieve your marketing goals.

Conclusion

Diligent, accurate marketing expense management is impossible in a spreadsheet. In Plannuh, it is highly automated, clearly visible, and easily editable.

Contact us to learn how you can get your expenses under control and maintain a real-time, accurate, team-sourced understanding of the state of your budget, and the complete life-cycle of your diverse expenses.

We hope you enjoyed one of the chapters of “The Next CMO”. If you are interested in the full book you can download it here!

{{cta(‘3f34ef64-f9ae-475f-b272-6f35d3e0c322′,’justifycenter’)}}